Google is now a huge, world-dominating corporation who control a lot of what we do online.

It’s considered one of the Big Four tech companies alongside Apple, Amazon and Microsoft, and like the others, is frequently in the news for misdemeanours as authorities wrestle to keep them in check.

On the surface, they only do good. Google provides us with software, devices and tools which makes our daily lives so much easier. We’re spoilt. And yet, is there a price to pay for these technological advances? How honest are these corporations, truly, and how do we ensure we as a populace benefit from their technological advances, at the same time as shielding our privacy?

Their search engine controls the lives of many; with 5.6 billion searches a day it is a source of income for thousands. Whilst this embraces the wonders of the modern age, it also means thousands lose business when it changes its algorithm, and so their levels of secrecy are understandably a constant hot topic.

Publicly, they state they hold user privacy close to their hearts but as you look closer, their hearts may, in fact, be digital too.

Read: Google is not a meritocracy

Google’s road to opacity

Founded in the autumn of 1998, Google was the thought-baby of Stanford Uni students, Larry Page and Sergey Brin. Its rapid growth quickly saw it surpass being simply a search engine, and today it offers everything from work and productivity products, cloud storage, maps, translation tools, IM, photo-editing and more.

Initially, Google was admired for the way it quickly brought a lot of goodness to the world, whilst simultaneously building tools that turned insane profits. It was the envy of other Silicon Valley entrepreneurs that led to the likes of Facebook upping their game to compete. Now, as the jaws of the competition begin to snap at one another, and criticism is rife, there are questions surrounding how transparent Google is being with its users, and how ethically it got to the status it holds today.

Rising to such heights requires a bulldozer approach, no doubt. However, with much press about antitrust, privacy concerns, censorship, tax avoidance and search neutrality, the microscope has swung to early signs of opacity.

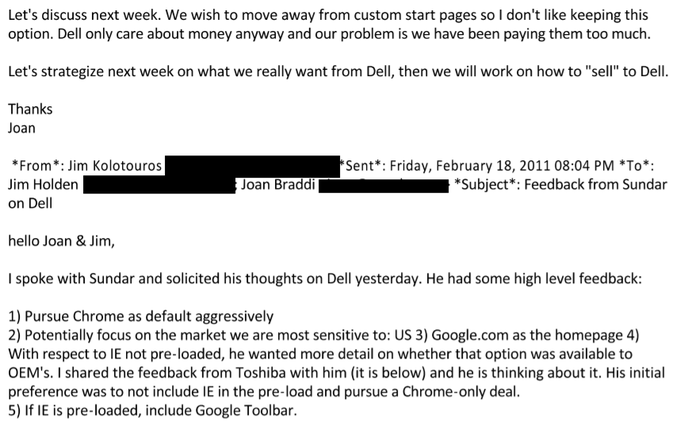

For example, emerging from old internal emails is information which demonstrates the aggressiveness of Google’s strategy towards market share. The emails talk about how they want to ensure Dell machines ship with Chrome and Google Search as the defaults. It outlines backup plans of installing Google toolbars if Dell insists on Microsoft’s Internet Explorer, and sets the foundations for the anti-competitive practices it was fined for by the EU in 2019.

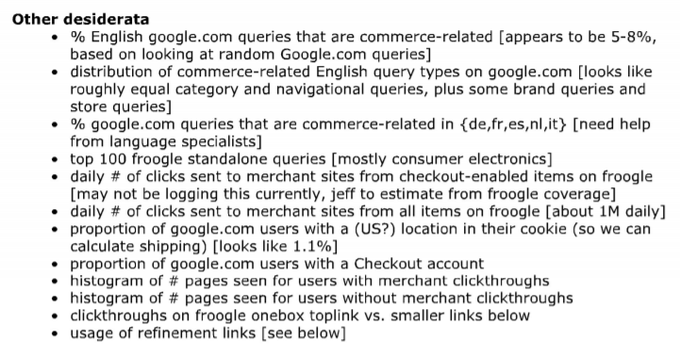

There’s also evidence to suggest their buying spree between 2005-2015 was to some extent a defensive maneuver against Microsoft and Yahoo. Similarly, further internal documents imply things they’ve repeatedly stated they don’t track, such as the % of clicks Google sends to other websites vs. their own properties, is in fact, tracked.

Why transparency is imperative

Google works hard to keep in conversation with their users. They’re transparent about their latest trend data, how they ensure quality in the SERPs and their mission has always been simply “to organise the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.” But as a multinational super business with a huge turnover, their motives may not always align with our own.

The problem with there being even a shed of uncertainty surrounding the clarity with which Google operates is down to the huge number of businesses that rely on their transparency.

Google’s ranking system has always been a serious focus for those who make their living from it. PPC, SEO and digital marketing experts spend large chunks of their time anticipating the search engine’s next moves in order to ensure their businesses operate at maximum efficiency. So it’s understandable that they expect nothing but honesty about what impacts rankings and what doesn’t.

However, whilst Google often announces their changes like the reduction of visibility of search terms shown in reports, they still cause frustration amongst advertisers. In these cases, Google frequently cites privacy with user’s interests in mind, yet why it leads to the loss of transparency into a large amount of ad spend, one can only wonder how it is in fact helping.

In fact, there are countless other examples of PPC managers being left blindsided, such as the recent sudden removal of all physical location data. The more changes like this that happen and get blanketed under the term ‘privacy’, the wider the glurf between our two shores becomes.

An addictive money machine

Technology is designed to be addictive so we keep coming back for more. And it’s important that we come back for more, so tech companies have a business.

The trending Netflix documentary The Social Dilemma emphasises this point over its hour and a half long deep-dive into big tech and its motivations.

An example that features towards the very beginning shows a man who was part of the Gmail team at Google; he called to question the fact none of the 50+ designers working on the look of the inbox were thinking about how to make it less addictive. He said that, for him, it was obvious that there was a moral responsibility surrounding those who create these tools to make it easier for users to switch off from them.

He put together a presentation calling on his colleagues to make this a priority, and got a great response, even from Larry Page himself, but then nothing happened.

We’re now in a world where the decisions designers make about something as simple as the way an email notification looks makes a huge impact on people’s lives. The statistics back it up: we spend 6.3 hours a day checking our emails, with 9 out of 10 people checking their work email outside of work.

Social media is worse still, with addiction affecting 210 million people worldwide. We see the designs of these platforms reinforcing similar addictions which are based on fundamental human psychologies – something we don’t stand a chance against.

For instance, we all want to feel important and the ‘typing’ feature of Whatsapp, or the ‘three dots’ on others, tell you you’re the focus of someone else’s attention, albeit momentarily. The ‘you’ve been tagged…’ notifications play into classic FOMO and make it difficult to resist opening up your Facebook app to take a peek.

Even the ‘pull down to refresh’ feature on news feeds emulates the slot machines in Vegas; you never know what may appear next.

Every aspect is designed to make you click and the Gmail team example sums things up quite well. Everyone agrees that technology addiction is damaging, but it’s too convenient and keeps us too doped up on dopamine for us to really want to move against it.

For Google, creating a Gmail inbox that was less aesthetically pleasing, less convenient and addictive, would go against their goals. Never mind the 2 billion people that would be affected by it; it would impact their bottom line and so is a no-go.

Google is a business at the end of the day, so the expectation that they would be transparent about how addictive their products are when it’s not a legal requirement is a little naive.

Advertising as a priority

In 2019, Google’s revenue stood at $160.74 billion. Of this, $134.81 of it was from advertising.

When people think of social media, they wonder how these giants are so rich. After all, these apps are free. How do they make money when their customers pay nothing? Well, their users aren’t their customers: their advertisers are. And that makes the users the products.

Google’s interests lie in making advertisers happy; those who can predict user behaviour most accurately sit at the top of the tree, and in order to make the most accurate predictions, you need a lot of data.

People worry about tech companies selling our data, but that’s not in their interests. Data which can be used to create models of human behaviour, which can then be used to influence real-world events such as the midterm elections, is very valuable. When companies are holding this level of power, it’s not enough for them to regulate themselves.

In congress, Kelly Armstrong from North Dakota questioned Google’s decision to close YouTube’s ad platform to any non-Google ad buying tools under the name of protecting user privacy. She accused Pichai of using privacy as a rhetorical shield: “What your company is really doing,” he said, “is using it as a cudgel to beat down the competition.” Google already has a lot of control over digital advertising and seems to be taking further strides to advantage itself.

How big is too big?

Antitrust is the premise that we want businesses to compete to offer the best products at the best price, but without getting so big that they crush or absorb the competition and then no longer have to worry about the customer because their profits are a sure-thing.

It’s what Google has been under scrutiny of since 2011 as they own every step in the complex system which exists between advertisers and consumers and which rivals state creates an unfair advantage. They have been accused of prioritising its own products and using the fact 9 out of 10 mobiles run on its android technology to strong-arm partners into installing its apps as defaults.

How Google’s growth has impacted its transparency can be seen in its behaviour with digital ad platform, DoubleClick, which it bought in 2007. Upon purchasing, Google promised it would never merge its data with that of DoubleClick’s.

Yet this changed in 2016, something which “destroyed anonymity on the internet”. Congress stated that what had changed in that time was Google’s enormous gains in market power. Essentially, they had grown so big that they no longer had to care what their users thought.

As Google’s market share continues to grow exponentially, there’s also a growing worry that antitrust will become a bigger issue; we have almost no laws about data privacy.

Unlike the press and television, online is a relative free-for-all. The EU is currently pursuing a Digital Services Act which would allow them powers to investigate how tech companies police illegal content as well as how they collect and use data.

Currently, they have to trust a company’s word regarding anything to do with disinformation, and that’s not enough when it comes to public interest.

However, as the last EU rules that govern the internet were set over 20 years ago, we may have to wait a little while for any rules to come into play. This is why transparency is so important – we only know what Google tells us and if they omit certain aspects, we’re entirely unaware of the full picture.

Is everything about data collection?

We’re living in a world where we are profitable when we’re addicted to our screens – this cannot be denied. And so, it’s important to question whether it’s in the interests of corporations like Google to be truly transparent. Of course, on the surface, it’s key for them to be seen as on our side, but the realities seem increasingly different.

Comparing Google’s behaviour to the likes of Microsoft also can’t be helped: Microsoft are curiously open about a lot of issues, including what goes into Bing’s ranking factors and transparency of authorship. Microsoft appears to be taking strides to grow their market share, but with Google as such a dominant force, it’s unlikely they’re quaking in their boots. Is this another step towards them having a monopoly on the internet?

Read: Bing vs Google: A Comparison

Furthermore, Google has been cited as like “dealing with a teenager” as they “don’t follow the norms that other businesses do. Google will tell you one thing and do something different.” It’s important that rules come into force, sooner rather than later, that keep this tech adolescent in check, before it becomes a fully-fledged adult.